ANSWER: Reputable, distinguished and unbiased expert analysts around the world have cited the existence of a pilot shortage for years. Indeed, every major airline has cited lack of pilots as one reason for flight cuts. Consulting firm Oliver Wyman estimates that US pilot demand will exceed supply by more than 12,500 by January 2023. The University of North Dakota forecasts a shortage of 14,000 pilots by 2026. Boeing’s Pilot and Technician Outlook 2021-2040 said, “with the dual impact of a smaller qualified pilot pool and accelerated retirements, it is expected that regional pilot shortages and strong competition for qualified pilots will re-emerge within the next few years.” Cirium data cited by CNN indicate that 500 regional jets (or more than one quarter of the regional jets in operation in 2021) have been parked. While demand is soaring, 71% of U.S. airports have lost air service, with an average loss of 22.4%, losing more than one of five flights they had before the pandemic.

ANSWER: No. While pandemic workforce influences sped up the pilot shortage, the shortage began developing long before the pandemic. The COVID pandemic accelerated the retirement bubble, as 5,000 – 6,000 pilots accepted union-brokered early exit packages from major airlines. However, pilots accepted these exits in April and May of 2020 and were required to be within two years of retirement to accept a package. This means these pilots would have needed to retire this year. While the pandemic accelerated retirements, these pilots would have retired by now anyway.

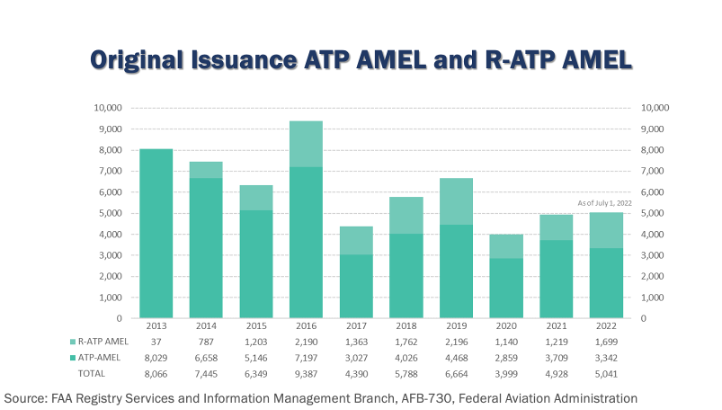

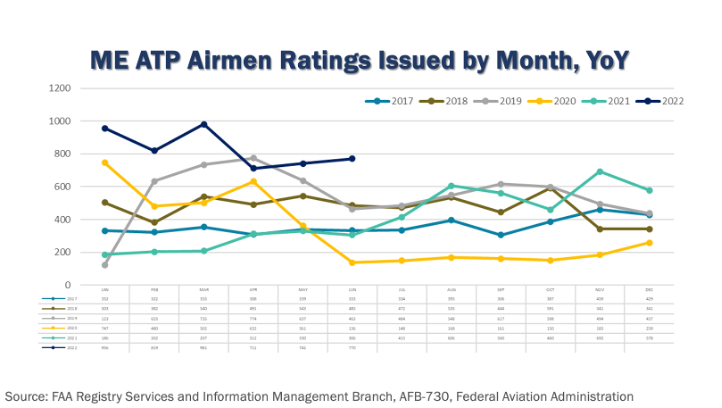

While the majority of regional airlines did not offer early exits, major airlines are recruiting pilots heavily as demand has returned, and are primarily drawing from regional airlines. In turn, regional airlines have turned to a pipeline of newly qualifying applicants. If the pipeline of new pilots were healthy, regional airlines could replace departing pilots with new entrants; however, there are far fewer new pilots in the pipeline (6,336 new pilots per year, on average, as reported in the FAA’s Registry Services and Information Management Branch, AFB-730) than would have been needed to fill airline ranks (14,500 openings per year per Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). This supply imbalance existed prior to, and irrespective of, early retirements and pandemic early exits merely accelerated these impacts. Unfortunately, being unable to find pilots, airlines are parking jets and suspending service despite near pre-pandemic air travel demand.

ANSWER: The pilot shortage is primarily impacting regional airlines, most of which did not offer early pilot retirements. Additionally, airlines accepting PSP funding agreed to forgo involuntary furloughs and involuntary pay cuts. While PSP funding fell short of covering airline total payroll costs (covering about 60% of payroll costs) and travel demand plunged to a fraction of the norm under CDC travel restrictions, pursuant to the requirements of PSP, any and all cost savings necessitated by those cost realities had to be voluntarily agreed to by employees. Major airlines and their union partners brokered voluntary exit packages for senior pilots that featured early exit packages as a means to avoid deeper pay cuts being needed from remaining employees. Without the Payroll Support Program, unsupported companies facing such unprecedented demand shock would have endured draconian, market-driven consequences. Indeed, massive furloughs, mostly involuntary, would have taken place, and those airline employees would have been eligible for unemployment insurance supported by taxpayers. From approximately 70,000 estimated working pilots in early 2020, about 5,500 major airline pilots accepted early exits and no airlines required involuntary pay cuts or furloughs from front line staff.

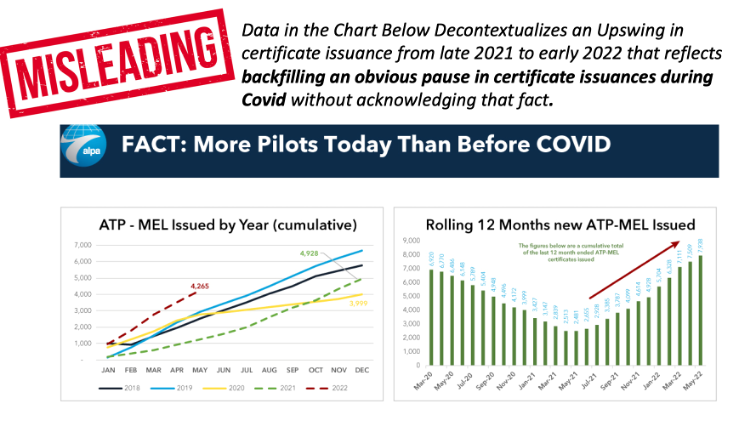

ANSWER: The chart above, which showcases newly issued Airline Transport Pilot (ATP) certificates, is missing important data that provides context and explanation for the uptick in new FAA-issued certifications. Over the past decade, FAA’s Registry Service and Information Branch, has reported an average of 6,335 ATP and Restricted-ATP (R-ATP) certificates annually. Yearly issuances, however, plunged during the pandemic, dropping below 4,000 in 2020 and below 5,000 in 2021. As training institutions resumed training and qualifying pilots in late 2021 and early 2022, the FAA began processing a backlog of pandemic-disrupted certificates. This has pushed the issuance rate higher than usual, although the rate has since slowed some, as expected. The two charts below provide the full picture of the yearly issuance rates, and the impact that the COVID-19 pause in certification had on FAA’s issuance of new pilot certificates. The chart above also ignores the government-forecasted need for new pilots (14,500 openings per year per BLS.)

ANSWER: No. This is another instance of manipulating data by omitting key variables; in this case, the data was left unsegmented. For example, an ATP pilot remains an ATP pilot at age 65, even though they are no longer eligible to fly part 121 airline operations. Fully 37% of total ATP certificates in the FAA’s Civil Airmen Database, used to create that talking point, are ineligible for hire by airlines in some way, whether they are older than age 65, are not a U.S. Citizen, or do not hold the required medical certificate. Once these known disqualifying factors are applied, just 107,469 ATP pilots are actually eligible for part 121 operations. The vast majority of these pilots are already working–seniority lists for the legacy, regional, low cost, national, and large cargo carriers (which doesn’t include business aviation or charter operations) total more than 97,000 pilots. At most, fewer than 10,000 potentially-qualified pilot applicants remain. With the Bureau of Labor Statistics forecasted average openings of 14,500 each year for airline and commercial pilots, the shortfall is already present. Additionally, these figures cannot account for disqualifying factors that do not present in the FAA database, like piloting skill, check-ride failures, disciplinary actions and pilot record reports, type and recency of experience, instrument proficiency, criminal records, DUI citations and more. There are not enough eligible airline pilots to meet demand and the only parties denying this have a vested interest in preserving the shortage, despite its devastating consequences for smaller communities.

ANSWER: That’s not the correct figure or statement. The United States Treasury Department made PSP payments totaling $50.1 billion to the 10 largest air carriers. The other 395 passenger air carriers shared the remaining $3.4 billion. The total is $53.1 billion, not $63 billion. Additionally, funds dispersed through the PSP covered approximately 60% of airline payroll costs during the pandemic. The program had strict requirements on how the money could be spent and funds could be used only for payroll costs (defined as employee wages, salaries and benefits). PSP was authorized to avoid massive involuntary airline furloughs during the peak COVID crisis. Participating airlines were prohibited from making involuntary workforce or other pay cuts during the agreed period and all cost savings efforts had to be voluntary. While most regional airlines did not offer substantial early exits to pilots, major airlines and their pilot unions negotiated to use exit packages for pilots approaching retirement to bridge the gap between PSP payroll coverage and payroll costs as demand dropped 97% during the CDC travel restrictions. Unions backed this move to avoid pay cuts to a larger body of airline workers. The coalition is reassured by ten audits of the program by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, which reported an overwhelming level of compliance with the PSP requirements.

ANSWER: In a high-demand travel period like we are experiencing, there is no financial reason for airlines to reduce flights. Quite simply, at times with high demand when nearly all planes are full, airlines could make more money with more flights. There just aren’t the pilots available to operate those flights and unfortunately communities are losing service as a result.

According to the Regional Airline Association, 66% of the nation’s airports are too small to support air service by larger airlines. These locations are served by regional airlines who provide the only source of scheduled passenger air service. Because regional airlines are the career entry point for airline pilots, their pilots are recruited by major airlines to meet their workforce needs. The lack of pilots will continue to result in parked airplanes, reduced routes and frequencies, and in many cases, cancelled passenger air service altogether.

Unfortunately, many communities have already been hit hard. Since 2019, a review of Official Airline Guide (OAG) published schedules shows that 71% of U.S. communities have lost air service. On average, communities losing air service experienced a 22.4% percent decline in the number of flights.

ANSWER: According to regional jet manufacturer Embraer, 56% of airports with commercial air service (371 total airports) are only served by 50-seat jets. Those smaller jets, together, feed passengers to larger jets by connecting them to larger hub airports. In fact, even major cities have a significant amount of regional service to smaller cities. Chicago O’Hare airport has 62% of its flights going to regional cities. Dallas-Fort Worth (47%), Charlotte (56%) and Houston Bush (55%) are other examples of big hubs dependent on small community air service to fill flights, maintain jobs, and add to the local economy. Without smaller jets feeding the hubs, air service options at larger airports will also be impacted. While small communities are losing the most, everyone loses when air service goes away.

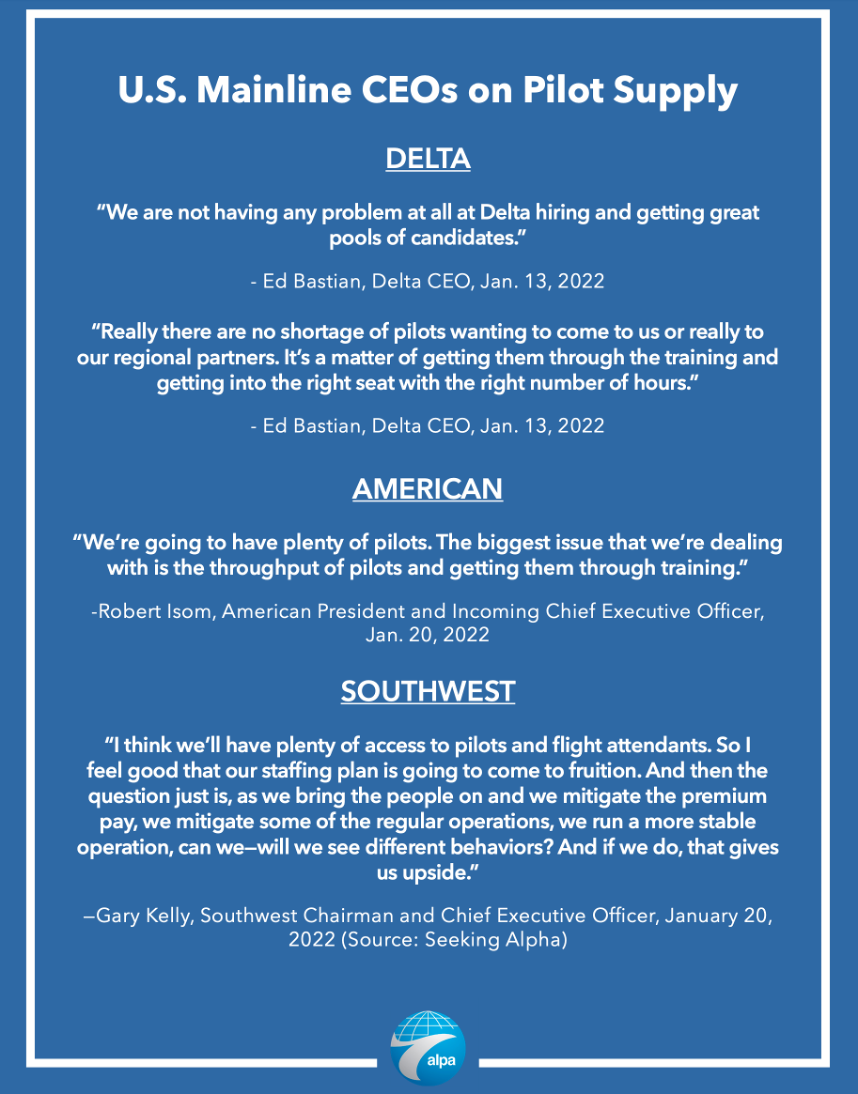

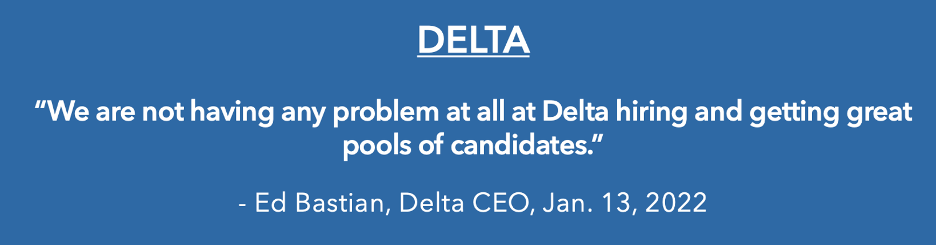

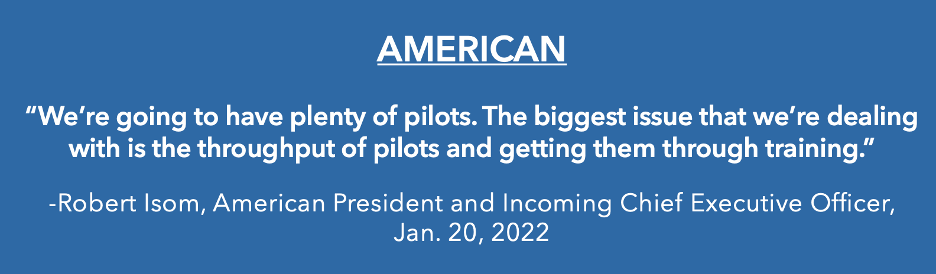

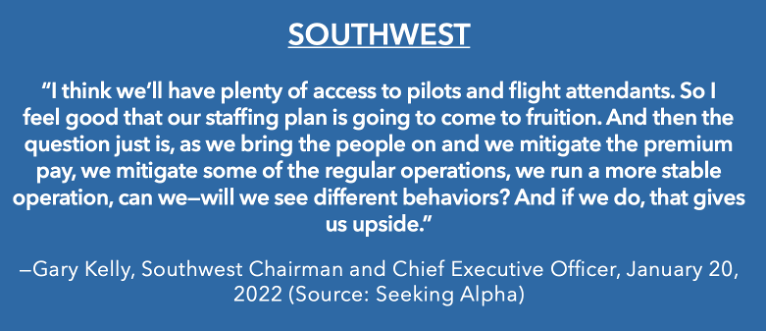

ANSWER: Once again, ALPA has omitted data, or in this case, failed to include adjacent sentences, in a way that mischaracterizes the speaker. Additionally, several of these quotes were not actually spoken by the person they were attributed to. See the ALPA infographic below, then scroll down for the actual, full quotes in question to understand how the speakers and their statements were distorted.

While the quote above was attributed to Ed Bastian, CEO of Delta, the actual quote was given by Delta President Glen Hauenstein, who went on to say that the pilot shortage was impacting its regional partners.

Full Quote: “We’re hiring at the mainline somewhere between 100 to 200 a month presently and we expect that pace to continue for some period of time, certainly through ‘22 and into ‘23. We don’t want to get too far ahead of ourselves, but that’s the pace that we’re hiring at. And everyone else in the industry is hiring, too. So it’s not just Delta. We are not having any problem at all at Delta hiring and getting great pools of candidates. That’s viewed as the premium airline that employees in general, but particularly pilots want to come work for, which we’re thrilled that. But it is having the impact at the regionals, as you mentioned. We are down flying in the first half of the year on some of the regional carriers given some of the staffing challenges we’re facing, primarily because of pilot hiring.”

The quote above was correctly attributed to Robert Isom, CEO of American Airlines, but ALPA failed to acknowledge that Isom went on to remark on the pilot supply imbalance at regional carriers.

Full Quote: “…We’re going to have plenty of pilots. The biggest issue that we’re dealing with is the throughput of pilots and getting them through training. We’ve invested an incredible amount of resources and having training assets ready to go. Those are all coming online. And again, from a mainline perspective, we will be able to supply all that we need. The imbalance is really going to be played out in the regional carriers. And on that front, like other carriers, we’re going to have issues as well. We have them right now. We’re working very hard on that. It’s impacting us to a certain degree, but we’re going to do everything that we can to make sure that it’s not a material impact over time.”

While the quote above was attributed to Gary Kelly, Southwest Chairman, the actual quote above was from Scott Kirby, CEO of United. Bob Jordan, not Gary Kelly, also responded to the question, and discussed the moderation of capacity, which he said was “all about staffing.”

Full Quote from Scott Kirby: “Our approach in 2022 really is to just accept that the environment that we’re in currently might be the environment that we’re in for a while and go ahead and plan the airline and staff the airline like that. And so that’s what you’re seeing with respect to the capacity adjustments here in 2022, is just making the assumption that let’s still assume things are going to get better until they actually do.

So we have a very aggressive plan to go hire people. I think our wage rate increases, especially in the front line for the ground, will help us accelerate our staffing. I think we’ll have plenty of access to pilots and flight attendants. So I feel good that our staffing plan is going to come to fruition. And then the question just is, as we bring the people on and we mitigate the premium pay, we mitigate some of the regular operations, we run a more stable operation, can we — will we see different behaviors? And if we do, that gives us upside.”

Full quote from Bob Jordan, new CEO of Southwest:

“Well, and Sheila, you add back just sort of what’s the constraint. At the beginning of the pandemic, it was all about managing down your capacity because of demand. Demand fell 97% and then stayed down 70% for a long time, so it was all about managing to lower demand. Well, that’s not where we are today, again. Sort of back to the fourth quarter, we had stronger — obviously, strong revenue, strong yields, strong fares, strong demand overall. And that’s when business demand down 50%. So very strong leisure. In my mind, leisure has returned to 2019. Obviously, that was interrupted by Omicron, but I’m confident that the leisure demand is restored. And we just need to get the staffing levels to the point where we can operate our aircraft, operate them reliably, produce the kind of operational performance that our customers need and want and deserve, and it’s just going to take staffing to do that. And obviously, that staffing in a strong labor market, which is why you saw us raise our starting wages. But no, to me, the moderation is all about staffing, not because of any concern over demand. And so then again, you layer on to the fourth quarter, the 50% recovery in business continues to recover in 2022, and we’re hopeful that it recovers by the end of the year to, say, down 10 to 20. I think we’ll have plenty of demand. It’s all about getting the hiring to restore the capacity.